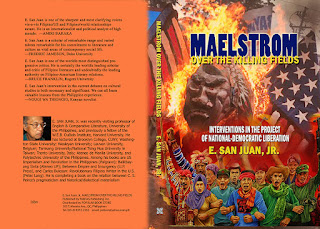

Maelstrom Over the Killing Fields: Interventions in the Project of National-Democratic Liberation. Quezon City, Philippines: PANTAS Publishing, 2021.

[Available from POPULAR BOOK STORE, also <amazon.com>]

A Book Review by Paul Gabriel L. Cosme, Macalester College

E. San Juan, Jr.’s Maelstrom over the Killing Fields brings its readers through a concise yet critical historical montage of Filipino struggles from the times inside the Spanish convent to American Hollywood and during today’s struggles against Rodrigo Duterte’s impunity and war on the poor. Consisting of eight vastly different essays, San Juan focuses on themes, ideas, and situations that encompass a wide variety of interests and viewpoints on the Filipino struggle.

The beginning essays provide the historical topography of how the Philippine nation developed as a series of struggles between local classes and colonial forces, namely the Spanish, American, and the Japanese. San Juan traces briefly how each colonizer established and operated its hegemony. Where Spain put minimal effort to co-opt the local population, the United States crafted a neocolonial strategy of assimilating the elite classes through a wide variety of entryways, primarily, education. During the Second World War, the Japanese wreaked havoc throughout the archipelago, but none of this chaos and violence would cease as the Americans reclaimed the Philippines. Even after independence, the United States’ grip on the Filipino nation remains strong.

San Juan also highlights the historical phenomenon of the Filipino diaspora and Overseas Filipino Workers (OFW) as crucial to revitalizing the mass consciousness towards Filipino determination. By engaging the problems of OFWs, a critical pedagogy may be developed to trigger “acts of remembrances and ultimately deliver collective redemption.” San Juan’s illustration of Fanny Garcia’s “Arriverderci,” which is set during the peak of the Marcos-induced exportation of Filipinas, provides us a glimpse of this pedagogy as to how putting a critical eye on the diaspora may reenergize the study of culture in the homeland.

In one of his reflective essays, San Juan provides us a narrative that concerns the failure of communication in the cultural landscape of his alma mater, the University of the Philippines – Diliman. Through the tradition of semiotics and literary theory, primarily through Charles Sanders Peirce, the essay shows us issues of communication by pondering the faculties’ reception of San Juan’s “Man is a Political Animal,” an ironic riff on Aristotle’s idea of the human being as a “political animal.”

He also takes prominent cultural figures, specifically Jose Rizal and Nick Joaquin, and combs through their works, contributions, and controversies that relates them to the project of national liberation. By taking apart Rizal’s revolutionary novels, San Juan highlights how Rizal reflects on and encapsulates the intersectional struggles of gender, class, and the nation into an allegorical network that is all connected to Sisa’s character. Through this exploration, San Juan uplifts Rizal’s subversive achievement in contributing to a revolution through a dangerous occupation during those times—writing. Meanwhile, San Juan takes up Joaquin, whom he claims as the artist of the Hispanicized Filipinos and ilustrados and argues that his focus on the ordeal of the “urbanized Indios of Metro Manila” fails to address the plight of the Filipino holistically as he excludes “the peasantry and the whole proletarian world of serfs, women, tribal or indigenous communities marginalized by Spanish and US colonial domination.”

San Juan also does not spare discussing nationalism, its development, and the history of struggles and resistances that surround it. He traces various actors and events in Filipino history that contributed to the nationalist project, which consists of the ilustrados, the propagandists, the revolutionaries, the proletariats, artists, and intellectuals, which span from the Spanish colonial era to the Marcos dictatorship. He illustrates figures such as Isabelo de los Reyes, poet Benigno Ramos, and Salvador Lopez, among others. San Juan also highlights the contribution of Filipina writers towards national insurgency. He engages works by Lualhati Bautista, notably her Dekada 70, Bata, Bata, Paano Ka Ginawa?, and especially her Desaparesidos. A notable critic of the Marcos dictatorship, Bautista attempts to articulate the Filipina experience during those dark times, and San Juan uplifts Bautista’s efforts to rekindle our collective memory and to make visible the disappearing bodies and neglected stories of Filipinas in the national struggle.

San Juan drives the nail with his exegesis of Duterte’s impunity and war on the poor while connecting the historical lines between the political drama and circus between the United States and the Philippines. From Duterte’s exhibitionist Anti-Americanism to his bloody rampages, San Juan discusses how counter-movements and resistances in the homeland and the United States challenge the violence and human rights abuses of Duterte’s regime in hopes of stopping the degradation of the Philippine democracy.

One can say that San Juan’s Maelstrom over the Killing Fields distills his scholarship and writings about the Filipino project towards self-determination without sacrificing depth and brevity. His interventions on the project of national liberation provide a succinct yet varying accounts of the “Filipino people’s durable tradition of counterhegemonic revolution” that are informative and compelling to all readers. Filipinos, especially intellectuals and compatriots, may find San Juan’s work refreshing, challenging, and seriously provocative. But above all, Maelstrom strongly reminds us of the complicated yet rich history of struggles over the making of the Filipino nation and its psyche.